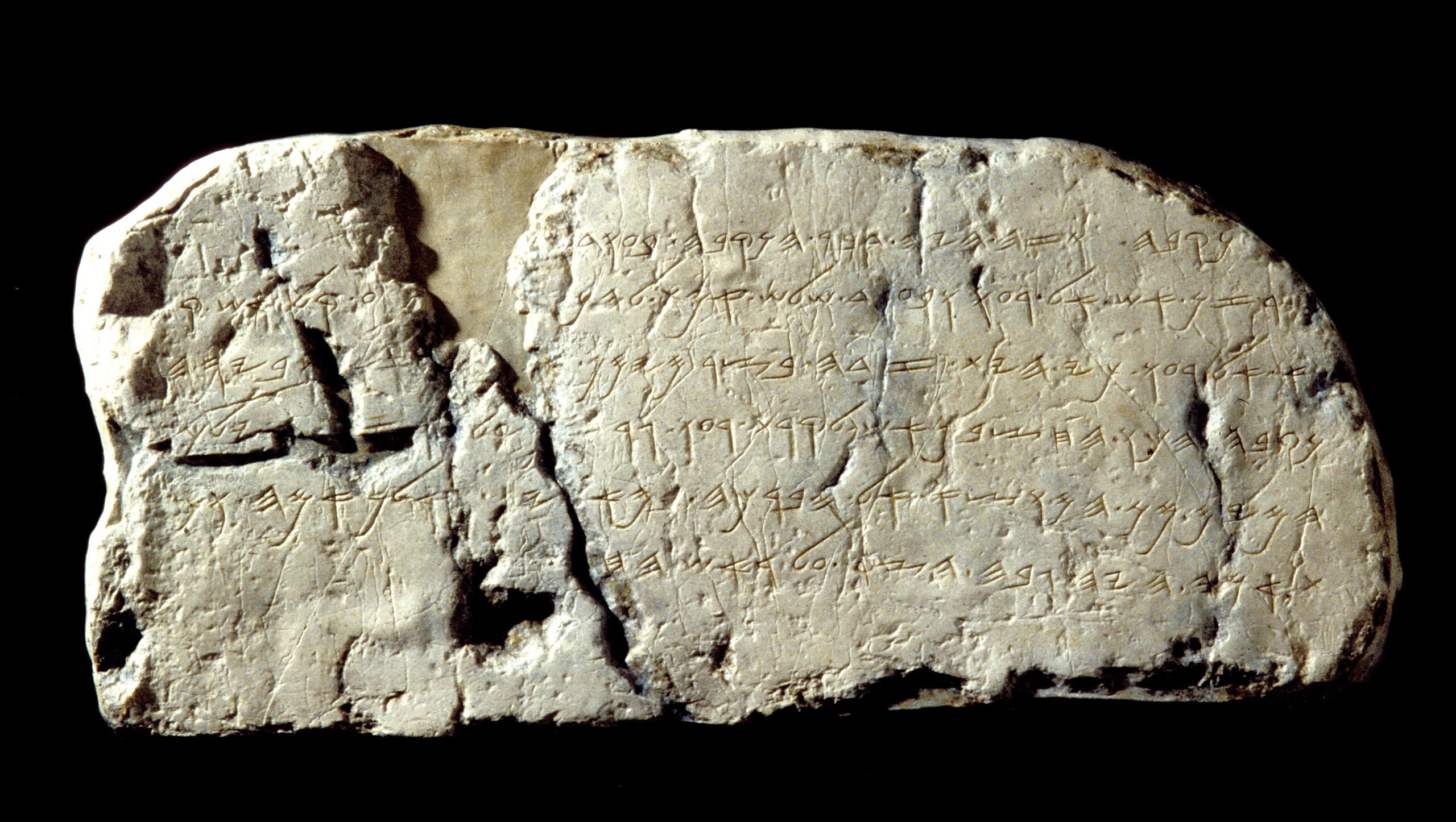

This Hebrew inscription dates back to the Israeli period (eighth century BCE) and was discovered by two children in 1880 a few meters from the southern exit of the tunnel known as “Hezkiah’s Tunnel”. It is currently displayed in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, Turkey, and this is because it was discovered during the Ottoman rule. The inscription describes the dramatic moment of an encounter between the two groups of masons who worked on the tunnel. It was engraved in the rock close to the exit of the tunnel, and not at the meeting point between the groups. The fact that it was inside the tunnel raises an interesting question: No people walked inside the tunnel, and therefore people could not see the inscription. So why was it engraved in a place where no one would see it? (As long as water is used for drinking, passing through the tunnel may cause contamination.)

Discovery of the inscription

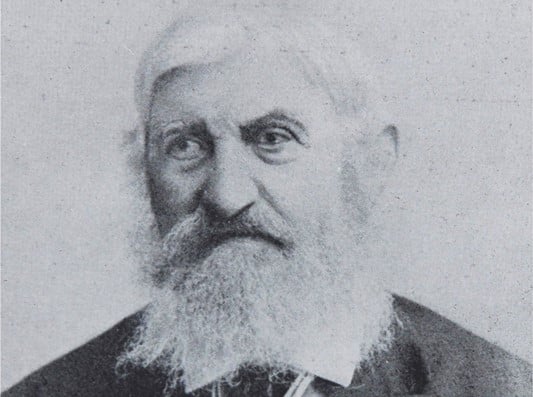

It all started in 1880 when a boy named Jacob Eliyahu and his friend decided to check, if it was possible to pass along the entire length of the canal. Six meters from the pool, he slipped on some rocks and fell into the water. When he got up, he noticed the letters on the walls of the tunnel. It is possible that the matter would have gone unnoticed if Jacob had been an ordinary child. But Jacob was a student at the school of none other than the renowned German researcher, architect and resident of Jerusalem, Conrad Schick.

When the student told Schick what he saw, the teacher followed him back to the tunnel, and thus began the saga of the Siloam Inscription. Schick related the story of the discovery:

I had only a faint hope that we would ever know the details of when the tunnel was carved. But now, something has occurred, due to which I believe that there is a chance that this mystery will be solved. A short time ago, one of my students passed by the tunnel, and on the south side of it, he stepped on rocks that were in the water and fell into the water himself. As he rose, he noticed letter-like markings on the sides of the tunnel. I set out to inspect the discovery with the necessary instruments, and after careful inspection, I found a very smooth section, east of the rock, 25 feet away from the (southern) entrance, and around it the rock remained in the form of a frame […] Opposite it, on the west side, a niche was carved into the rock, where the person who carved the tablet placed his lamp. There is an inscription on the tablet of 8 or 10 lines […] As far as I could judge, the letters are Phoenician [ancient Hebrew script].

The discovery made waves all over the world. Schick became famous as the finder of the inscription, but the boy himself remained anonymous. Years later, Bertha Spafford Vester, daughter of the founders of the American colony in Jerusalem, claimed that this was her adopted brother, a child of Jewish origin whose family immigrated from Turkey and converted to Christianity.

The content of the inscription, engraved in ancient Hebrew script typical of the end of the First Temple period (end of the 8th century BCE), proves that the impressive plant, carrying – just as the Bible describes – the water of the Gihon “to the west of the City of David” (2nd Book of Chronicles, 32:30), is none other than Hezekiah’s handiwork, hence its name nowadays “Hezekiah’s Tunnel”. Since the Bible clearly states that the water flowed “to the west of the City of David”, there is no longer any doubt that the eastern hill is indeed the City of David – the ancient nucleus of Jerusalem.

A quick look at the tunnel carved over half a kilometer long in the thick of the rock arouses wonder in every visitor, and explains why the Bible precisely chose this enterprise to perpetuate the memory of King Hezekiah, but the inscription contributed additional details that further added to the wonder and provided a fascinating glimpse into the feelings of the workers who actually did the work.

[…][ends] the tunnel. And this is the story of the tunnel. While […] the axes were against each other and while three cubits were left to [cut?]… the voice of a man called to his counterpart, for there was zada in the rock, on the right [and on the left] and on the day of the tunnel (being finished) the stonecutters struck each man towards his counterpart, axe against a[xe] and the water [fl]owed from the source to the pool for 1200 cubits. And the height over the head of the stone cutter[s] was [100?] cubits.

The reconstruction of the events according to the inscription presents the following picture: two groups of workers were engaged in the quarrying of the tunnel at the same time. One started from the spring, and the other came from the direction of the pool. The groups advanced towards each other underground.

The description of the last moments of the quarry conveys the feeling of tension in the hearts of those digging. After long days of hard work, would they be able to complete the task? Would the groups meet? A special excitement passes through those doing the work upon hearing “the voice of a man calling his neighbor” (the voices of the carvers from the other side) and the appearance of the “zada” (crack?) “in the flint on the right and on the left”. At last, they received a sign that their efforts were not in vain, and that they were standing a mere step from the finish line. With a feverish effort, the hewers hit ax upon ax in opposing directions, until finally they met. The result, which is also the culmination of the story from the point of view of the author of the inscription, is “haNekiba” (“the tunnel”) (That’s how it is commonly read in the inscription.). That is to say, it is the opening of the hole of the meeting that allowed the flow of water from the source to the pool. The completion of the complex engineering plant at such a great distance and at such a great depth underground was a great achievement that was surely received with happy applause at the ceremonial occasion in which the plant was inaugurated.

A number of questions arise regarding the inscription. The meticulous design and the official style, taken as it were from one of the books of the Bible, leave no doubt that this is a royal inscription. However, unlike other royal inscriptions in the ancient Middle East, whose main purpose is to clarify the names of the kings, there is no mention of a king or any other high-ranking personality in the Siloam Inscription. Why does the author of the inscription not even mention the name of Hezekiah as the Bible does? Another question that has troubled the researchers is: Why was the “commemorative sign” engraved at the end of a dark tunnel that, for the most part, no human walks?

There are several possible solutions to these questions: It is possible that part of the inscription, the lines of dedication to the king at the beginning, has been corrupted over time. And perhaps there was another inscription outside next to the pool, where Hezekiah’s name was boldly emblazoned.

Another possibility is that this inscription was not intended to glorify the king, and conversely, it was intended to express the king’s appreciation for the workers who participated in such a complex operation. If this is the case, here is a rare revelation, and definitely rare among leaders – of the humility of a king who honors the workers and gives up on glorifying himself!

We will not know definitive answers to these questions. The upheavals through the area of the tunnel’s origin corrupted the remains of the past, and even the inscription itself is no longer in its place. 10 years after its discovery, a Greek antiquities dealer from Jerusalem tried to steal the valuable relic, and detached the inscription from the rock wall. During the quarrying work, the inscription was broken into several pieces. Fortunately, Conrad Schick made a plaster replica earlier that preserves its original form. The Ottoman authorities tracked down the merchant, confiscated the inscription, and transferred it to the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul. It is there to this day. Unfortunately, the inscription is not permanently displayed to the public. The correct place of the inscription is of course the place of its discovery in Jerusalem, but the Turkish government did not respond to the request of the Israel Museum to transfer the inscription to it, even on loan, on the occasion of the 3000th anniversary celebrations of Jerusalem in 1996.